- Home

- —

- Thurston Dart

- - Objets Dart

- - Dart Biography

- - Dart Remembered

- Little Feat

- Francis Tregian

- —

- Ingestre Hall

- Time Wasters

- Personal Records

- Album Covers

- —

- Performing

- YouTube Videos

- Sessions

- Arranging

- Tuition

- Music and Theatre

- Folk Club

- Special Occasions

- —

- A Life in Music

- Memorabilia

- Employment

- Qualifications

- Odds and Sods

- Contact

THURSTON DART - a biography

Greg passed away on 25 July 2020.

Donations in his memory can be made to British Heart Foundation.

His partner, Katy, will monitor his email if anyone wants to get in touch.

As no published biography of Thurston Dart exists, Greg decided to draw on his recollections and make use of the "Dartiana" he inherited to create this biography.

Thurston Dart

Dart was an eminent harpsichordist.

Early Life

Robert Thurston Dart was an English musicologist and performer. His parents married on 31st March 1915 at the Church of St Mary, Kilburn, London. Bob was born in Surbiton, Kingston-upon-Thames, on the 3rd of September, 1921 and was an only child. His father, Henry Thurston Dart, was an employee of Lewis, Lazarus and Sons (metal merchants) for twenty years, rising to be in charge of their Freight department. However in 1929 (when Henry was 39 and young Bob was 8) L. L. & S. decided to close down their consumer shipping department. Consequently Henry's employment ceased. He had about £2000 available in capital and considered starting a business but he also applied for work with the White Star Line and Imperial Airways. Times must have been hard. In the end he opted to train as a schoolmaster. At Shoreditch College, during 1930-2, he studied for the University of London Teacher's Certificate. Bob's paternal grandfather was Henry John Baker Dart, a musician. His mother, Elisabeth Martha Orf, was from Devon and is said to have had Belgian and Russian ancestors. Her father was Michael Orf, a corset manufacturer. Bob's father died in 1954 and his mother died on 5th May 1965, aged 76 years. Apparently Dart later told Lady Susi Jeans, that "he had two Austrian grandparents" (which she reported in the Galpin Society Journal volume XXIV, p.2.). So he seems to have been aware of his international family tree.

Education

Dart attended Hampton Grammar School and was in Pope's House. It seems he was a year ahead: that is, in the Spring of 1937, when the average of his form (6A) was 17, Bob's age was only 15-and-a-half. His Higher results were not uniformly good but he got a Distinction in Music. There were several key formative musical influences on him at school. He sang in the choir at Hampton Court which kindled his love of English music. Singing madrigals with the Hampton Court choristers in the local madrigal society, he met Edmund Fellowes and this stimulated his interest in the editing of early music. As a schoolboy he also attended a summer school at Bingley, Yorkshire with Arnold Goldsborough who made a deep impression. He was involved with school productions of Gilbert and Sullivan including singing Second Bridesmaid in Ruddigore! At the Christmas 1937 production of Iolanthe he played the piano in the school orchestra. As an adult he spoke warmly of school, according to his good friend Allen Percival (in Source Materials and The Interpretation of Music). Upon later becoming a governor of the school he proposed student representation on the Governing Body.

Chubby youth

In 1933 Dart won medals in the Solo Singing and Vocal Duet class at Wimbledon Music Festival and at the Kingston-upon-Thames Music Festival he won a medal in the Pianoforte Duet Under 14 category. He sang "Clear and Cool" from The Water Babies on the BBC's Children's Hour on 11th February 1936 and appeared again on 24th March (singing Elizabethan songs) at 2 guineas a time - the beginning of a long association with the BBC! He lived at this time at Devon Lodge, Portsmouth Avenue, Thames Ditton, Surrey.

As a teenager and young man Dart composed chamber and keyboard pieces, and a 3 movement orchestral suite. His "Opus 1" was a Passacaglia in C minor for organ. These survived him, having been deposited in a trunk at his last London address in Welbeck Street for several decades.

Bobbie Dart was a chubby youth and then a good-looking, photogenic young man, but he grew large and a little ungainly. However, when he was in Form 6A his cap size was 7½ so he was not particularly big-headed! He was not sporty. Years later I had an interesting talk with him about participation in sport when I was at King's College, London. I had been missing Wednesday afternoon music workshops – excellent and worthwhile though they were – to play rugby for the College. I was summoned to see the "Prof". My come-uppance was widely anticipated! However he said that they had never had a member of the Music Faculty representing the College at rugby before and were very proud of me so please continue.

As a youthful organist

In 1938-9 Dart spent a year at the Royal College of Music to study as an accompanist. He also studied harpsichord with Arnold Goldsborough, whom he had met as a boy at the summer school in Bingley. Then in 1939 the family moved to Kingswear on the River Dart in Devon. In the 1939 Torquay Music Festival organ competition he played J. S. Bach's Trio in E flat (1st movement) and Mendelssohn's Prelude and Fugue in C minor, scoring 92 marks out of 100. He got maximum marks for the Mendelssohn but the adjudicator criticised his choice of stops in the Bach and "some occasional faltering with feet". The summary was "all most excellent work and musically played".

In 1939-42 Dart attended the University College of the South-West of England, in Exeter, and studied Mathematics, taking an external London BA degree (second class honours) in June 1942. In the same year he took the Associate of the Royal College of Music (ARCM) diploma in Pianoforte Accompaniment.

Royal Air Force

In the RAF

1942-5 saw war service. Prior to serving in the RAF Dart was a Junior Scientific Officer at the Ministry of Aircraft Production. In the RAF he became a statistician and operational researcher with the Strategic Bombing Planning Unit. He served under Air Vice Marshall (later Sir) Basil Embry at Headquarters No. 2 Group. Embry wrote about taking command of 2nd TAF (Tactical Air Force):

I next called for an assessment of the average bombing error of the Group over the past nine months. I was told that to calculate this from the many photographs of bomb bursts would be a tremendous task, and did I really need it, because the bombing of the Group was excellent, as I could see by examining the photographs they held in the operations room. I replied that I was sure these photographs revealed some very good bombing, but I wanted to know what was the average error of all the other bombs not shown in the photographs on display. I explained to Dart, our operational research scientist, exactly what I wanted and after about a fortnight of long hours of work, with some outside assistance, he assessed the bombing error of the Group. I did not retain the the exact figure in my records, but memory recalls that it was something like twelve hundred yards. I was appalled but not disheartened!

— from Mission Completed, Sir Basil Embry, Landsborough Publications Ltd, 1956.

Subsequently Dart was promoted to Scientific Officer on 1 April 1944 and granted an Honorary Commission as a Flight Lieutenant in the Administrative and Special Duties Branch of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve on 20th April 1944.

In November 1944 he was injured in a plane crash. His letter to his parents described the event.

No 55 Mobile Field Hospital,

R.A.F.

British Liberation Army.

Dear H & M,

A somewhat involved week has passed. First an explanation of my (temporary) address. Whilst flying back to U.K. earlier this week, one engine of the aircraft I was flying in cut on us and we had to force-land in the middle of a field staked, wired and mined against air-landings by the Hun long before D-day. We were all very fortunate in our pilot who made a magnificent job of our landing and we escaped with odd cuts and bruises and so on. So after an hour or so we were picked up by some army people stationed not far away and taken to a Field Dressing Station from whence they took us on to this very pleasant hospital to be looked after – and looked after is the right word: plenty of cigarettes, chocolate and so on. The food is excellent: the nurses charming and the attention over-whelming. I don't anticipate a long stay (I might almost say unfortunately, because I'm very comfortable here!) but I'd like to have a line from you to this address if you can spare the time. So don't worry about me as I shall be quite myself again in a week or so.

You'll be pleased to hear that I've met some very musical people who live not far from my proper station – and, moreover, they're very keen on old music and have a couple of viols and some recorders. So I look forward to some pleasant evenings with them soon.

No more news for the moment – and please excuse the awful writing!

Love and love,

B.

A letter from the Ministry of Defence, dated 14 August 1975, described the event thus:

On 19 November 1944 Flight Lieutenant Dart sustained injuries whilst on a communication flight in an Oxford MK II aircraft which crashed in Calais Marck airfield. He suffered from arm injuries and was admitted to a mobile field hospital and later moved to the RAF Hospital Wroughton on 5 January 1945. F/L Dart was then transferred to the RAF Hospital at Cosford on 8 January 1945. After about two weeks Robert Thurston Dart was finally transferred to the RAF Medical Rehabilitation Unit at Loughborough Leicestershire for further exercise treatment.

RAF Hospital Wroughton, near Swindon, Wiltshire, had been built by the RAF and opened in 1941. Dart finally returned to duty in May 1945.

For his efforts and achievements Dart was Mentioned in Dispatches. After relinquishing his Honorary Commission on 1 August 1945, he applied to resign from the Ministry of Aircraft Production in order to go to Cambridge for post-graduate statistical research work at the University. His resignation was accepted by the Ministry and became effective from 30th September 1945.

Brussels

From Dart's collection, Charles van den Borren on the right

Convalescing at the end of the war, he had met Neville Marriner, who had been wounded in the army, at a recuperative nursing home in Swanley in Kent. Dart was still primarily a mathematician at that time but he told Marriner that he wanted to go to Brussels to study with the great Belgian musicologist Charles van den Borren. Despite his arm injury he decided on a musical career and so spent his ex-service gratuity on a course of study with van den Borren. Dart lived as his family guest in Brussels. Van den Borren had published Sources of Keyboard Music in England in 1913, which was an important influence on Dart's subsequent work. Dart was fond of the Low Countries and learned French, some Flemish, later Dutch.

During the period when he was travelling over to Brussels Dart and Marriner met occasionally. They had a mutual friend in Anthony Hopkins who got them playing together at his house. Marriner and Dart played a wide range of music together, including a lot of contemporary music. Dart was a first-rate keyboard player, Marriner said.

Post-War

In 1946 he returned to England and lived with the Moules in Royston, Hertfordshire (at 46, London Road). Henry Moule was a Music lecturer at Cambridge. Dart was his research assistant. Bob became an assistant lecturer in Music in 1947, and therefore was awarded the official Cambridge degree of M.A. on 4th December 1948.

On 20th August 1947 he wrote to the BBC in his typically rich, imaginative and witty style.

Dear Sir,

It is too hot to compose an elegant preamble in an appropriately impersonal and severe style. Coming to it roundly then, without hawking and spitting, this is to ask for an opportunity to give an audition as a harpsichordist and/or clavichordist.

I stupidly omitted to inform the BBC of various performances of mine at the galleries of the Royal Society of British Artists earlier this year, for it is always pleasant to be heard in congenial conditions and surroundings.

Good wine needs no bush, they say, but this, like so many proverbial sayings, is curiously difficult to verify. As a diffident vintner may I therefore submit two small boughs. The Times music critic found space for some pleasant comments. I enclose a cutting, which I should be glad to see again when you have done with it. So much for my musicianship. The scholarliness of my work is best attested by the fact that I have just been honoured with the position of an assistant lecturer in Music in the University of Cambridge. I shall also be contributing to the new edition of Grove's Dictionary.

My boughs, I see, are becoming not a bush but a positive shrubbery. I shall check the spreading undergrowth, therefore, by subscribing myself,

Yours very truly,

R. Thurston Dart

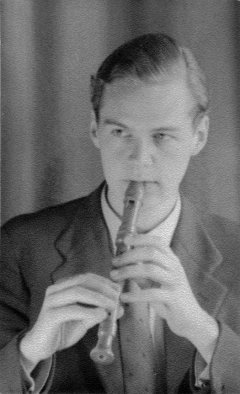

"an excellent performer

on the recorder"

He was auditioned and in 1948 had his first engagement (since childhood!) at the BBC, playing "early keyboard music on the Continent" in the series A History In Sound Of European Music. He met Susi Jeans there as she was on the same programme. They were to become very fond friends and musical collaborators (they played on two harpsichords for example at Victoria & Albert Museum Concerts in 1955-6). Dart continued to make regular broadcasts over the years as a performer and speaker on the Third Programme.

Setting out on his career as a harpsichordist, he soon got known as a very creative and inventive extemporiser with great panache, very at ease with singers and an excellent accompanist. Dart formed a harpsichord and violin duo with Neville Marriner, which led to the formation of the Jacobean Ensemble. In 1957 He was awarded the Cobbett Medal for services to chamber music.

The Galpin Society was formed in October 1946 "with the object of bringing together all those interested in research into the history of European musical instruments" it stated. Dart was the first Honorary Editor of The Galpin Society Journal, the first volume of which appeared in 1948. It described itself as "an occasional publication" and was, in fact, to be an annual volume. As a contributor Dart averaged an article a year up to 1968. In the 1971 volume Susi Jeans said that the early and lasting success of the Journal "was due to his selfless and untiring efforts" ("Robert Thurston Dart, 1921-1971. An Appreciation by a friend", Galpin Society Journal volume XXIV, pp. 2-4). He was succeeded as Editor by Anthony Baines in 1955.

Dart excelled at all keyboards. As well as still having "a pleasing singing voice" and being "an excellent performer on the recorder", according to Susi Jeans in the Galpin Society Journal (volume XXIV, pp.2-3), he was also a keen player of viols (and acquired a chest of viols of his own).

Playing the viol

In 1948 Dart was living at Reynolds Close, Girton, Cambridge and in 1949-50 at 7 Adams Road, Cambridge (the house of Alexis and Jill Vlasto). He played in a consort of viols there. "Shortly after he came to Cambridge - he was at the time occupying a room in our house - we invoked the aid of my uncle, Marco Pallis, and a Cambridge consort was formed. Dart acquired a fine Jaye treble. Viol-playing with his friends, fallible amateurs or beginners though they might be, remained one of his great pleasures." (Alexis Vlasto, "Obituary: Robert Thurston Dart", in Chelys: The Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society, vol.2, 1970, pp. 3-4.) Allen Percival was first a music undergraduate at Cambridge and then Bob's first research assistant (in 1950). They lodged with the Vlastos, sang madrigals and played viol consorts. They also played at University Music Club Saturday concerts and drank in "The Eagle" pub.

Musicologist

On the 18th June 1949 a Memorandum of Agreement had been made with Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. for The Interpretation of Music. Dart was to get 10% royalties on sales. This book was to have immense success. It was written while he was at Jesus College in 1953 and published in 1954. Dart said his "greatest sense of indebtedness is towards someone who did not see the book until it was published: Professor Charles van den Borren, of Brussels. Constant in his friendship as in his advice and guidance, he has been to more than one young scholar a pattern of knowledge matched by musicianship, of kindliness blended with humility, that outstrips emulation just as it inspires devotion." I think it could be said that van den Borren was a role model for Dart, who demonstrated many of the same qualities. In 1964 on 17th November, on the occasion of van den Borren’s ninetieth birthday, Dart dedicated a manuscript (“copie unique d’apres L’original”) of three pieces by Alcetur to van den Borren.

In 1949 Dart became Secretary to the Editorial Sub-committee of the Royal Musical Association and then a founder member of Musica Britannica in 1950. The name was initially opposed by Encyclopaedia Britannica until a legal Agreement was made between Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Royal Musical Association in 1951.

The founder members of Musica Britannica were:

Editorial Committee

Mr. Frank Howes (Chair)

Professor Edward Dent

Dr. Edmund Fellowes (died 21 December 1951; replaced in 1952 by Professor Gerald Abraham)

Professor Anthony Lewis

Professor Jack Westrup

Mr. Robert Thurston Dart (Secretary)

Management Committee

Mr. Frank Howes (Chair)

Mr. Cedric Glover

Professor Anthony Lewis

Mr. Vere Pilkington

Mr. Robert Thurston Dart (Secretary)

Dart saw through some thirty volumes. "Let there be no mistake about it, it was Dart's scholarship and energy that guided the Musica Britannica volumes through the press. He undertook the chief task of detailed editorial direction, checking and consultation and carried it out with tremendous thoroughness", said Anthony Lewis (Music and Letters Vol. 52, No. 3, July 1971, p.236).

Dart was Secretary to Musica Britannica committees from 1950 to 1965, by which time he was delegating to William Oxenbury. (Bill's handwriting can be seen in the accounts from September 1963.) Bill then remained Secretary for forty years, putting in a tremendous amount of work, not least in proof-reading very many volumes.

Performer

Dart with Louise Hanson-Dyer in Amsterdam

From about 1950 Dart began his association with Éditions de L'Oiseau-Lyre of Monaco. The patronage of Dr. Geoffrey Hanson and his wife Louise Hanson-Dyer, with whom Dart became close friends, boosted his reputation internationally as a recitalist and recording artist. He made dozens of recordings, mostly of solo keyboard music and his Froberger recording won an Académie Charles Cros Diplome Grand Prix du Disque.

Dart had played with the Boyd Neel Orchestra from 1948. When Boyd Neal stopped directing it Bob took over and it metamorphosed into the Philomusica of London. Dart was artistic director from 1955-9. The Leader (Concert Master) was Granville Jones and later Neville Marriner. Dart introduced a new sound and had bows specially made for the purpose and new scores based on his scholarship. He chose Bill Oxenbury as the Secretary and General Manager to run it from 1956-9. “5.55” concerts at the Festival Hall were some of their successes. There were many modern premiers of early music pieces. Dart resigned in 1959 with ill-health, to reduce his commitments and to concentrate on Musicology and his burgeoning interest in music education. He went to Taormina, Sicily, to convalesce.

1961 he recorded Purcell's Dido and Aeneas with Janet Baker in the leading role. She had earlier performed the role of Second Witch at Ingestre Hall in 1957!

Dart contributed a number of articles to the fifth edition of Grove Dictionary of Music (1954) including Notation. He was a devoted scholar, tireless reader and researcher with a prodigious energy and output. He had the precise mind of a mathematician allied to a musical sensitivity. The goal of his scholarship was informed, expressive performance. He believed very strongly that practical music-making was essential to the heart of all music study and this paved the way for future generations of musicologists and performers. He tempered the more austere theoretical approach of, for example, the Dolmetschs with a open-minded approach to spontaneity and expression in performance. He used smaller forces, often single instruments per part.

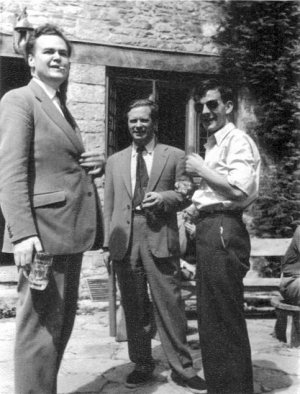

At the organ

with Neville Marriner

His new ideas and new performing editions did not meet with universal critical approval, however. “Nowadays he would be considered to be a messiah but in those days he was rather considered to be a trouble-maker”, said Sir Neville Marriner in a 1996 BBC Radio 3 broadcast. Nevertheless he gave tremendous vitality to the Early Music scene, which at that time could have been considered a little crusty and dull. "Those who may occasionally have been offended by his uncompromising, not to say imperious, ways must surely have realized that they were a manifestation of his passion for excellence in performance and precision in scholarship." (Alexis Vlasto, "Obituary: Robert Thurston Dart", in Chelys: The Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society, vol.2, 1970, pp. 3-4.) Dart had tremendous verve and a sense of fun. I remember him saying that operatic overtures were composed for the audience to talk through: so when he went to Covent Garden he followed authentic period practice!

Cambridge

In 1952 he became a full lecturer at Cambridge. He was first a member of Caius College, then Selwyn and finally in 1953 a Fellow of Jesus (with rooms of his own for the first time in his life). He revered Boris Ord, the choir master at King's College Chapel and it was at this time that he became friends with Bill Oxenbury, who was an undergraduate chorister.

In 1952 he also became a member of the Council for the Royal Musical Association and later a vice-president. He became a member of the editorial committee of the Purcell Society and in 1965 he was elected a member of the library committee of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. His club in London was the Savile, in Brook Street, very near where Handel had lived.

He went to the USA as a visiting lecturer at Harvard in 1954 – where South African composer Stefans Grové was among his students – and in 1967 went to Seattle, via San Francisco. He was widely travelled in Europe – Holland, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Italy, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary. However he didn't much enjoy travel, especially on his own. For all the solitary hours of study – perhaps because of them – he was a social animal, liked an audience and enjoyed having a good time.

Dartington 1956 with Bill Oxenbury (right)

On 26th June 1957, following the conversion of the University College of the South-West of England to the University of Exeter he was awarded the ad eundem degree of B.Sc. (what he would have got had the College been chartered when he was there). On 8th October 1958 he was admitted, as "Citizen and Musician of London" into the Freedom of the City of London.

He was a director from 1954 and eventually Chairman of Stainer & Bell (founded in 1907; publishers to the Royal Musical Association). In 1968, as Chairman he signed the memorandum appointing Bill Oxenbury a director. He revised the Fellowes editions of madrigals, lute songs and Byrd; and began the English Keyboard Music series and Invitation to Madrigals.

In 1962 Dart was elected to the Chair in Music at Cambridge, succeeding Patrick Hadley. He was not head of department and couldn’t reform the syllabus as he wanted. However he had a profound influence on his many students during his Cambridge years, both as a teacher and performer. Christopher Hogwood turned pages for him at the harpsichord in the early 1960s and marvelled at his inventiveness. Dart was also prolific as an editor and recording artist at this time.

It seems Dart never had his own house and he did not drive. This presumably spared him a number of expenses and time-wasting chores. Given his prodigous output and work-load this is probably significant.

In Cambridge he had a room in the house of William Milo Keynes, 3 Brunswick Walk - his "country hideaway". Milo was the third son of Sir Geoffrey Keynes, and his wife Margaret Darwin, daughter of Sir George Darwin. He was a great-grandson of the naturalist Charles Darwin, and a nephew of the economist John Maynard Keynes. He died in Cambridge on 18th February 2009 at the age of 84.

London

After two stormy years as the Chair in Music at Cambridge, Dart was invited to King's College, London. The University of London Board of Studies in Music had recommended that a full-time Chair and Faculty of Music should be established in the University of London and that this should be at King's. Dart became King Edward Professor of Music in 1964 and was able to create a new teaching faculty and replace the University syllabuses with radically revised ones. In the undergraduate syllabus music was placed in the context of its time. There were compulsory papers on the history of instruments and on set periods including the twentieth century. The technical musical exercises of the old syllabus were reduced. Indeed Dart put a sign up at the entrance to the Music Faculty proclaiming "Abandon counterpoint all ye who enter here"! This did not, however, stop him from giving interesting lectures on it.

At the clavichord

The presence of Thurston Dart attracted post-graduate students of outstanding calibre from all over the world. He emphasized the study of printing and the process of diplomatics (dealing with the study of old documents), the musical sources being pre-eminently important to his methods. "The essence of his work was his preoccupation with musical sources themselves. Most of his hypotheses – and many of them were audacious – arose directly from the study of a source, its preparation, ownership and use. He trained a generation of scholars not only in clear, critical thinking about musical topics but also in palaeographic, diplomatic and bibliographic skills, and emphasized the study of the history and techniques of printing. He was an impulsive, generous man and a dynamic teacher." (Ian Bent, The New Grove Dictionary of Music.) He gathered a varied team of full- and part-time staff, including Ian and Margaret Bent, Frank Dobbins, Jeremy Montagu, Nazir Jairazbhoy, Viram Jasani and the composer musicologists, Geoffrey Bush, Edward Lockspeiser and Anthony Milner. In 1965 he was made a Fellow of the Royal College of Music.

Professor Dart had the support of General Sir John Hackett, the Principal from 1968, who, like Dart, was a brilliant, witty man, a courageous, imaginative, clear thinker, and also a very practical leader.

In London Dart stayed with Bill Oxenbury at 2 Eyot Gardens W6; then from 10th March 1966 at

5 Gordon House, 37 Welbeck St, W1 on the corner of Marylebone High Street and New Cavendish Street - his "London pied-a-terre". Here he had a fairly large room with a desk, a record player, a clavichord, a wardrobe, book shelves and a single bed.

He could and would cook, he smoked and he liked a gin and tonic (which was also kept in the office at KCL as well as being freely available in Welbeck Street, where much wine and whiskey were also drunk).

Bob and Bill were a great team with complementary skills. Bill was as hard-working and imaginative at admin. as Bob was at research. Bob would come down to London for the week (or at least the middle of it) and go back to Cambridge for the weekend. The wonderful Dodo Pad (house desk diary) moved into the flat in 1967. Bob's entries in this are often witty and facetious. In private his attitude to being a Professor was very unstuffy - "This is Reading Week hooray"; "End of the 'orrible term"; etc! After Bob's death Bill Oxenbury lived there for another thirty years, as did the Dodo Pad! In fact it became so essential to the synchronisation of "The Hotel" and Bill's group of close friends that it was the main item on Bill's Christmas shopping list and I and others relied on his gift of it year on year. (It is an interesting historical footnote that Lord Dodo was later to move to Perranporth in Cornwall, as was I. But this was purely co-incidental, though it may say something about Cornwall.)

Influence

Dart's lectures and seminars were meticulous and stimulating, if sometimes a little cryptic. I once attended a lecture he gave which ranged from Chinese music (he was learning Chinese at the time) to the melodies of hymn tunes and Elgar. He "demonstrated" by means of hypotheses, arguments and diagrams that "Nimrod" suffered from being melodically and rhythmically overly repetitive. Afterwards there was the "oh dear, and I used to like it" sort of reaction from some of the more overawed undergraduates. My feeling was, after due pause, that this was either what we would now call a "wind-up" or at least contained an element of the Dart tongue in the Dart cheek. The message was, of course, in part, don't believe everything you are told, question things, back your own judgement, music is about much more than theory, ultimately it is about expression. And, as he said in a subsequent lecture, beware of proving too much by melodic analysis! Though reserved in his manner he was far from austere. For example in another lecture he introduced us students to P.D.Q. Bach and his "recently discovered works"! Challenging and imposing though he was, he would listen to a reasoned argument and give you his support if you held to your convictions.

He was a warm, amusing man, confident, good company and likeable. He had the gift of seeming totally interested in the person he was speaking with. He took trouble with his appearance, was dapper and neat. He wore colourful waistcoats for concerts. He wore contact lenses. His dignity was only a little compromised by his slight ungainliness. There was no hiding the fact that his feet were big, even in good shoes! He was generous with both knowledge and possessions. He was soft-voiced and quietly spoken but with great authority because he was so physically and intellectually impressive. A very original mind, he studied subjects not hitherto in the mainstream of musicology. He challenged accepted ideas and institutions. He had stature without arrogance.

In fact for all the impression of being the daunting, large and formidable Professor, he was a kindly man and, I think, fond of his students. He was asked to be Godfather to four children: Peter Dominic Vlasto, Simon Roberts (son of the late Tony Roberts, of Jesus College), Hendrik Larsen (son of Jens Peter Larsen of Copenhagen) and the eldest son of Denis Stevens (the musicologist).

He was very formal, polite and correct. Undergraduates like me were addressed as "Mister". We obviously did not know his less formal side but we realised he was extremely generous. He started a William Byrd Fund to help students financially and, typically, persuaded the bank to let him sign cheques as William Byrd! He held fund-raising cheese and wine parties in the Faculty on William Byrd's birthday.

Dart had a large collection of musical instruments and a vast personal library of books, many of which were kept in the Faculty for others to use. He also collected manuscripts and early printed editions. He possessed an appreciation of fine art and assembled a large collection of modern drawings, paintings and sculpture. His taste in music was broad and he had a wide range of other interests and enthusiasms, including a penchant for science fiction and an admiration of De Gaulle.

Dart excelled at all keyboards

In a letter of 30th January 1968 to his solicitor and executors (in preparation for a new will) he said, "Of my musical instruments the one that's meant most to me is Tom Goff's clavichord." He was protective of this clavichord in the Music Faculty. With typical wit he put a notice on it saying "If your name is Dart, you are welcome to play this clavichord. If not, don't". Nevertheless, in his thoughts for a will he wrote: "I hope that this, like all the others, will be used - not treated as a museum specimen, to be seen but not heard!"

On a clavichord that we students were able to use he wrote a note saying

Always replace the rug,

To keep the instrument snug.

See that the fringe

Does not break the hinge.

Lift away from the wall

And do not scroop;

Then the legs will not fall

(Or droop)

[Vers is a curse.]

His influence was disseminated through his many students at Cambridge, London and Harvard who went on to hold eminent positions in the world of Music. These include: Ian Bent; Margaret Bent; Mary Berry (Sister Thomas Moore); Stanley Boorman; Robin Bowman; Philip Brett; Lenore Coral; Alan Cuckston; Lucy Durán; Leslie East; David Fallows; Peter Fletcher; Nigel Fortune; John Elliot Gardiner; Bryan Gillingham; Stefans Grové; Christopher Hogwood; Peter Holman; Margaret Laurie; Peter Le Huray; Laurence Libin; Richard Marlow; Davitt Moroney; David Munrow; Michael Nyman; Roger Parker; Allen Percival; Stanley Sadie; Benedict Sarnaker; John Stevens; Michael Tilmouth; Colin Timms; Brian Trowell; Peter Williams.

His main fields of scholarship were J. S. Bach; 16th, 17th, 18th century keyboard and consort music; and John Bull. He left five chapters of a book on Bull. In draft some 139 pages long, the work was not complete and Dart was not satisfied with it. All the papers were passed to Susi Jeans in 1974, by Bill Oxenbury, one of his executors (the other was Allen Percival), who made a condition that the Bull biographical material was not to be assumed to be correct.

The draft chapters are:

1. Biography

2. Gresham College

3. Bull's Art of Canon

4. The Paris Book

5. Royal Organist and Foreign Flight

These papers are now held in The Thurston Dart Archive at Cambridge University Library.

He took a stand on issues that he felt strongly about. He thought operational research methods (which he learned in war service) should be applied to the problem of what to do with the London orchestral scene and wrote to The Times (June 25th 1965) to say so and to criticise the report of Lord Goodman, then Chairman of the Arts Council. He also wrote an article in The Musical Times Vol. 106, No. 1470 (Aug. 1965), pp. 591-593, entitled "Musical Dinosaurs and Operational Research: Some Notes on the Goodman Report by Thurston Dart". He said of operational research (OR) in this article: "As a method of analysis it was forged in the furnace of war, in Britain 1939-45 ... Properly used ... there is no door OR cannot unlock, no dilemma it cannot help resolve."

He supported the Anti-Concorde Project (which began in 1966), especially on grounds of cost, arguing that the money could be better used on other things.

Final illness

Bob Dart seems to have assumed his cancer of the stomach was curable. He certainly gave that impression to others. He referred to "a little tummy trouble". Either he was very stoical or he was over-confident of recovery. He had made advance entries in the Welbeck Street flat Dodo Pad for weeks beyond the date when he died. The University of Cambridge had announced that they intended to confer on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Music.

At the start of 1971 he was recording his new edition of the Brandenburgs with Marriner and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. By the third day he had to lie down on a mattress in the studio between takes. His last ever performance, on 2 February, was the recording of the Adagio from a Sonata in G (Schmieder No. 1021), used as a slow movement for the Third Brandenburg Concerto. Neville Marriner states in the booklet for the CD set, "He played the continuo for the first movements of Concertos 2 and 4, and for the serene Adagio used for the slow movement for No. 3. I put him into the car which took him to the clinic at 5.30 p.m. and saw him no more." This was the London Clinic in Devonshire Place.

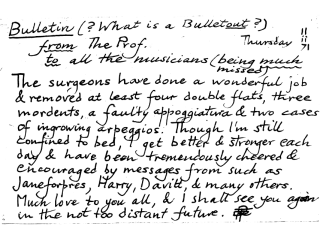

" Bulletin (?What is a Bulletout?) Thursday 11.ii.71 from The Prof. to all the musicians (being much missed) The surgeons have done a wonderful job & removed at least four double flats, three mordents, a faulty appoggiatura & two cases of ingrowing arpeggios. Though I'm still confined to bed, I get better & stronger each day & have been tremendously cheered & encouraged by messages from such as Janeforpres, Harry, Davitt, & many others. Much love to you all, & I shall see you again in the not too distant future. RTD"

On February 11th he sent a cheery letter to the students at King's and asked to see them all. He did not make us feel that we were visiting a dying man. The reality was soon to prevail, however: he died on the 6th March 1971, aged only 49. His ashes, according to his wish, in the will he had only just written on the 26th of February, were placed in the family grave in Torquay. A Memorial Concert was held at St. John's, Smith Square on 3rd April, 1971 with music by Dowland, Corelli, Berio, Mozart and Purcell, played by some of his students and ex-students.

The Times obituary (March 8th 1971) said "In his combination of practical musicianship, penetrating intellect and elegant verbal expression, he typified the traditional virtues of British musical scholarship". Susi Jeans described him, in her Appreciation, as '"the 'Opheus Britannicus' of his time" ("Robert Thurston Dart, 1921-1971. An Appreciation by a friend", Galpin Society Journal volume XXIV, pp. 2-4). His enormous positive influence on musicology and the Early Music renaissance has probably still not yet been fully recognised.

Copyright Greg Holt © 2006-11