- Home

- —

- Thurston Dart

- - Objets Dart

- - Dart Biography

- - Dart Remembered

- Little Feat

- Francis Tregian

- —

- Ingestre Hall

- Time Wasters

- Personal Records

- Album Covers

- —

- Performing

- YouTube Videos

- Sessions

- Arranging

- Tuition

- Music and Theatre

- Folk Club

- Special Occasions

- —

- A Life in Music

- Memorabilia

- Employment

- Qualifications

- Odds and Sods

- Contact

Remembering Thurston Dart

Greg passed away on 25 July 2020.

Donations in his memory can be made to British Heart Foundation.

His partner, Katy, will monitor his email if anyone wants to get in touch.

"Mention the name of Thurston Dart to lovers of early music and their eyes light up. He was one of the most important innovators in the field, making an indelible impression as teacher, editor and recording artist." Quite so: well put by Bill Newman. Robert Thurston Dart was an outstanding musicologist, performer and teacher of immense importance to the development of the study and performance of Early Music. He has variously been called the Orpheus Britannicus of our time (by Susi Jeans), a Rennaissance Man (by Sir Neville Marriner) and the Sherlock Holmes of musicology (by Sir John Eliot Gardiner). It is now nearly fifty years since he died and yet his reputation and legacy continue to burgeon.

Born in London in 1921 (an only child), Dart had attended Hampton Grammar School where he sang in the choir at Hampton Court, which kindled a love of English music; and he sang madrigals in the local madrigal society, where he met Edmund Fellowes which stimulated his interest in the editing of early music.

In 1938-9 he spent a year at the Royal College of Music to study as an accompanist. He also studied harpsichord with Arnold Goldsbrough. Dart and Goldsbrough admired each other. Dart later said of him, "He was shaking up our lazy ideas about rhythm, phrasing and tempo in Bach's organ music decades before it became fashionable to do so".

In 1939 his parents moved to Kingswear (appropriately on the River Dart) in Devon, whence his mother had come. In 1939-42 Dart attended the University College of the South-West of England, in Exeter, and studied Mathematics, taking an external London BA degree.

Dart in RAF uniform

He then began his war service. First he was a Junior Scientific Officer at the Ministry of Aircraft Production and then in the RAF he became a statistician and operational researcher with the Strategic Bombing Planning Unit. In 1944 he was promoted to Scientific Officer and granted an Honorary Commission as a Flight Lieutenant in the Administrative and Special Duties Branch of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. He did sterling statistical work on bombing accuracy for Air Vice-Marshal Basil Embry.

In November 1944 he was in a plane crash in Calais and suffered arm injuries. He was very lucky to survive, especially as the landing field was mined! This must have further energised him to live life to the full and waste no time in pursuing his objectives. Convalescing at the end of the war, he met Neville Marriner who had been wounded in the army, at a recuperative nursing home in Kent. Dart told Marriner that he wanted to go to Brussels to study with the great Belgian musicologist Charles van den Borren who had published Sources of Keyboard Music in England in 1913. Despite his arm injury he decided on a musical career and spent his ex-service gratuity on a course of study with van den Borren, living as a guest of his family in Brussels. Van den Borren was to be a very important influence on Dart's work.

Returning to England in 1946 he became the research assistant to Henry Moule, a senior Music lecturer at Cambridge University. Moule, with his rigorous approach to research and interest in revising academic regulation, was another big influence on him. Dart was actually little qualified in Music at this stage: it was only by being appointed to a post at Cambridge that he was awarded an MA degree. Dart became an assistant lecturer in 1947 and in 1952 a full lecturer. He was first a member of Caius College, then Selwyn and finally, in 1953, a Fellow of Jesus.

He had energy, ideas, perception, knowledge and a questioning approach to the rather parochial, dull world of Early Music; and he had a cosmopolitan outlook - he had chosen to study in the Low Countries, which held particular musicological interest and where the Early Music movement was also to flourish. Post-war, the music scene was ready for innovation and change and he was a breath of fresh air.

He undertook prodigious amounts of work. The Galpin Society was formed in 1946 and Dart was the first editor of its Journal. In 1949 Dart became Secretary to the Editorial Sub-committee of the Royal Musical Association and then a founder member of Musica Britannica in 1950. He saw through some thirty volumes. He was Secretary to Musica Britannica committees from 1950 to 1965 and then Chairman. In 1952 he became a member of the Council for the Royal Musical Association and later a vice-president. He also became a member of the editorial committee of the Purcell Society and in 1965 he was elected a member of the library committee of the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

He was a director from 1954 and eventually Chairman of Stainer & Bell, publishers to the Royal Musical Association. He revised the Fellowes editions of madrigals, lute songs and Byrd; and devised the English Keyboard Music series and Invitation to Madrigals. He pursued the policy of keeping everything in print, though not without checking the sources first.

In 1949 he began a series of over fifty BBC broadcast talks, in addition to his broadcasts as a performer, though he later bickered with the BBC and at the end of 1963 withdrew his labour, temporarily from radio and permanently from television.

Dart post-war

The Interpretation of Music was written while he was at Jesus College in 1953 and published in 1954. It was written with directness, clarity and great authority, notwithstanding that Dart was only thirty-two and had only been a lecturer since 1947! Marriner called it "the handbook for all early music buffs". It stated, "The main concern of this book is with the process of turning notes into sounds." He skewered the complacent assumption that music had progressively evolved. "A composer of the past conceived his works in terms of the musical sounds of his own day." "Each style of composition is perfectly adapted to the particular resources at the composer's disposal: a commonsense principle that remains true throughout the history of music, and one that is the basis of the whole of the present book."

He was a devoted scholar, tireless reader and researcher with a prodigious energy and output. He had the precise mind of a mathematician allied to a musical sensitivity. The essence of his scholarship was his focus on musical sources incorporating palaeographic, diplomatic and bibliographic skills: and the goal of his scholarship was informed, expressive performance. He believed very strongly that practical music-making was essential to the heart of all music study and this paved the way for future generations of musicologists and performers. He tempered theorising with an open-minded approach to spontaneity and expression in performance. As a performer he was not pedantic about musicological theory: he was above all a practical musician who wanted to reach audiences by the vitality of his performances. Making music was at the core of his motivation.

In setting out on his career as a harpsichordist after the war, he had soon become known as a very creative and inventive extemporiser with great panache, very at ease with singers and an excellent accompanist. He formed the Jacobean Ensemble with Neville Marriner. He was also a keen player of viols. He can be heard playing treble viol on the 1959 Decca recording of Gibbons' "This is the record of John" with the Choir of King's College Chapel and David Willcocks.

From about 1950 Dart began his association with Editions de L'Oiseau-Lyre, revising their Louis and François Couperin editions, among others. The patronage of Dr. Geoffrey Hanson and his wife Louise Hanson-Dyer, with whom Dart became close friends, boosted his reputation internationally as a recitalist and recording artist. He made dozens of recordings and his Froberger recording won an Académie Charles Gros Diplome Grand Prix du Disque.

Dart had played with the Boyd Neel Orchestra from 1948. When Boyd Neal left Dart took over and it became the Philomusica of London. Dart was artistic director from 1955-9. The Leader (Concert Master) was Granville Jones and later Neville Marriner. Dart introduced a new sound and had bows specially made for the purpose and new scores based on his scholarship. There were many modern premiers of early music pieces as well as recordings on L'Oiseau-Lyre. However, Dart had taken on too much and, unwell with overwork, he had to relinquish his Philomusica role.

1961 he recorded Purcell's Dido and Aeneas with Anthony Lewis and the English Chamber Orchestra. Janet Baker was in the leading role. Dart had written to Lewis in January 1961 from Jesus College (prior to casting Dido), "I was reminded of the existence of Janet Baker, whom you may like to ponder over. I did a show with her some years ago, and was much impressed. She thinks she is a contralto, but in fact she is a weighty mezzo, with a very good colour to the voice. I cannot remember whether she has a top G; I think so."

In 1962 Dart was elected to the Chair in Music at Cambridge. He was not head of department and couldn't reform the syllabus as he wanted. However he had a profound influence on his many students during his Cambridge years, both as a teacher and performer. After two difficult years in post in 1964 he was invited to become King Edward VII Professor of Music at King's College, London. Though Dart could now spend more time in London he gradually performed less and less as he threw himself into his vocation as an educationalist. At King's he was able to create a new teaching faculty and replace the University syllabuses with radically revised ones. He greatly reduced the emphasis on technical excercises in favour of placing music in the broad context of its time. There were compulsory papers on organology (the history of instruments, world-wide, and orchestration) and on set periods including the twentieth century, which Dart thought was very important. These broad subjects embraced jazz and ethnomusicology, electro-acoustic music and the avant garde. Dart had always played a lot of modern music on the piano and had many recordings of it on disc. He arranged for students to attend the contemporary music festival Reconnaissance des Musiques Modernes in Brussels, with Boulez, Stockhausen, Nono, etc. From scratch, within a few years, Dart's efforts created the largest and most varied group of university music students in the country.

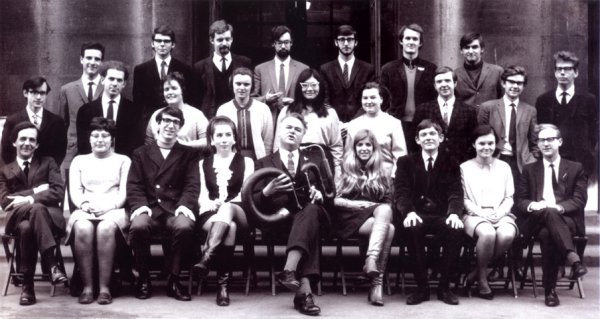

Dart (with serpent) - King's College, London, Music Faculty, 1967-8

My first direct contact with Dart was when I received a letter from him in 1968, offering me a place at King's College, signed in red ink. This was a first indication of the colourfulness of his personality! I first met him on 1st October 1968. I was an undergraduate fresher: he was King Edward VII Professor of Music. Naturally he made a strong impression on me. He was very formal, polite and correct. Freshers like me were addressed as "Mister". Respect! He was just 47 and at the height of his powers: but in fact he had less than two and a half years to live.

The huge step up from school was somewhat daunting and it was difficult for one to feel confident. It was, however, an exciting time to be a student in London. Within the month I was playing in the continuo section of my fellow student Peter Holman's new band Camerata.

For my weekly lesson at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama Dart arranged for me to do the then-new subject of Jazz with Howard Riley. Dart was himself interested in jazz and had several LPs, notably by Miles Davis on whom he gave a BBC talk. He could extemporise in many styles.

As undergraduates we obviously did not know his less formal side but we realised he was extremely generous. He started a William Byrd Fund to help students financially, holding fund-raising cheese and wine parties in the Faculty on William Byrd's birthday. The bank allowed William Byrd to have an account in his own name and Dart signed the cheques William Byrd! Dart was generous with his time and his property (books, instruments). He believed things should be used to help people and placed where there would be maximum benefit. He loaned his possessions or sometimes even gave them away if he was not using them himself. He wanted to help people and teaching became his priority.

Dart had tremendous verve and a sense of fun. He played us PDQ Bach records. I remember him saying that operatic overtures were composed for the audience to talk through: so when he went to Covent Garden he followed authentic period practice! It is a well-known fact that he put some people's backs up - but how could he not? He was a deep thinker and he was on a mission. As if he sensed that he was working against time he ceaselessly threw himself into trying to make improvements to things he felt passionately about. He was very clever and often right: it must have been frustrating for him at times, if annoying for others.

Large and imposing, he was a bit ungainly. He took trouble with his appearance (wore contact lenses), was smart and a little flamboyant. Dapper, but not effortlessly so. Always groomed, perhaps a little bit preened, you might say. At performances he wore colourful brocade waistcoats - one wag dubbed him the Liberace of the harpsichord! His signet ring, with his intertwined initials RTD, was always on his left little finger, perhaps to give weight to that finger when playing a keyboard. It was his left arm that had been badly injured. His very precise speech, with distinctive received pronunciation, matched his appearance. He was soft-voiced and quietly spoken with very precise, almost clipped, enunciation.

With zest and zeal he was intense and volatile; precise and logical; imposing and private; exacting and difficult; imperious and irascible; yet as Sir John Eliot Gardiner has said, gracious, helpful, inspirational and a brilliant scholar. A man of many sides and moods. For all the impression of being the daunting, large and formidable Professor, he was a kindly man and, I think, fond of his students. He worked too hard for the good of his health and perhaps his temper on occasion. But he appreciated company and liked to unwind: he enjoyed a drink and a smoke, cooking and food.

I would say he was a warm, amusing man, good company and likeable. Never dull. He exuded great authority because he was both a leader and intellectually impressive. A very original mind, he studied subjects not hitherto in the mainstream of musicology. He challenged accepted ideas and institutions. He had stature without apparent arrogance, though he could be rather grand and sometimes haughty, some said. He was somewhat larger than life. He put pressure on himself by setting himself very high standards in several fields. However, I felt his panache covered some vulnerability: his apparent supreme confidence perhaps hid a self-awareness of a limited ability to cope equally well with all types of people.

Dart was lucky in having some very loyal friends and supporters, such as Bill Oxenbury, Sir John Hackett, (later Sir) Neville Marriner, (later Sir) Anthony Lewis, Allen Percival, Louise Dyer, Susi Jeans and so on. (His friends called him Bob: Thurston, which had been passed down from his father, was used professionally.) In Cambridge he had a room in the house of Milo Keynes - his "country hideaway". In London, from March 1966, he had a room at Bill Oxenbury's flat in Marylebone - his "London pied-à-terre". It was a fairly large room with a desk, a record player, a clavichord, a wardrobe, book shelves and a single bed. In term-time Dart would usually come down to London for the week (or at least the middle of it) and go back to Cambridge for the weekend. He never had a home of his own. I don't imagine that this arrangement of ménages was ideal for a stress-free life, especially considering the pressures in London and the "politics" in Cambridge, never mind the personal relationships involved. In any case he may well have felt some underlying tension between maintaining his public image and having a discrete and discreet private life.

Dart playing the clavichord

On the surface primly formal, his emotional depths were usually below the surface, though obviously he expressed some of them musically in performance. Like many multi-facetted people his life was compartmentalised (even in the use of his own names). There was always some degree of division between his academic and performing roles; his public and private life too: and the sub-division of the latter between his London and Cambridge homes. (Les barricades mystérieuses?)

At the start of 1971 whilst recording his new edition of the Brandenburgs with Marriner and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields he succumbed to his "little tummy trouble" and had to go into the London Clinic in Devonshire Place with stomach cancer.

On February 11th he sent a cheery letter to the students at King's - "the surgeons have done a wonderful job & removed at least four double flats, three mordents, a faulty appoggiatura & two cases of ingrowing arpeggios" - and asked to see us all. When we saw him (in bed) he did not make us feel that we were visiting a dying man. The reality was soon to prevail, however: he died on the 6th March 1971, aged only 49.

The Times obituary (8th March 1971) said, "In his combination of practical musicianship, penetrating intellect and elegant verbal expression, he typified the traditional virtues of British musical scholarship. During his Cambridge years … he profoundly influenced the course of musical scholarship in Britain. He was a brilliant teacher, intellectually rigorous, but broadly speculative too … He always stressed the practical aspect of musicology, an attitude which his own work exemplified; at his best he was without peer as a harpsicordist [sic] … His continuo playing was a model of creative accompaniment."

"Dart's strength lay in the nice balance between the sensitive player and the ruthlessly precise mind of a mathematician" said Alexis Vlasto in his obituary. "For him the scholar's work was incomplete until the music was brought to life in performance with full knowledge of the composer's style and intentions." Marriner said,"He liberated the musicians, certainly in England and, I would have thought, also internationally".

This was a man who loved life, beauty, art, the pursuit of knowledge; a sensitive man, highly intelligent, gifted and musical. A brave man who took on challenges with the courage of his convictions and faced a final poor deal from the hand of fate with equal fortitude. The fact that he favoured musical communication over any theory he had developed shows how much he served music rather than promoted his own considerable musicological achievements. For all his hours with dusty documents he was essentially about communicating with people. The musical world was a better place for the contribution of RTD.

A Memorial Concert was held at St. John's, Smith Square on 3rd April 1971 with music by Dowland, Corelli, Berio, Mozart and Purcell, played by some of his students and ex-students.

Source Materials and the Interpretation of Music, a Memorial Volume to Thurston Dart, appeared in 1981, containing a substantial set of case-studies by some of his students reflecting his emphasis on the study of source material. It included a comprehensive Dart bibliography and discography. Dart had chosen research students to pursue particular fields that he considered needed work on. His influence was disseminated through his many students at Cambridge, London and Harvard who went on to hold eminent positions in the world of music, both as musicologists and as performers such as Munrow, Hogwood and Gardiner. His musicological clarity and elucidation were a major influence on Marriner and the orchestras he performed with. The invention of digital recording certainly helped the spread of Early Music as there had been little of it available on LP so companies were keen to record it for the new CD medium. The Dart influence has thus spread exponentially through the cascade effect of the many successful Early Music proponents who have vastly expanded the available repertoire.

The BBC have from time to time broadcasted a retrospective tribute programme on Radio 3 - Early Music Forum 7.iii.81; Mining the Archives 6.ix.96; BBC Legends 30.ix.01; Masterworks Artist of the Week (March, 2000).

A Chair at King's College London now bears Dart's name: the Thurston Dart Professor of Performance Studies chair. Laurence Dreyfus became the first Thurston Dart Professor in 1997. He wrote to me, "It is indeed a great honour to hold a chair that bears Thurston Dart's name, and the more I learn about Dart's years at King's, the more I've come to admire the man and musician". In 2001, on the fortieth anniversary of Dart's death, KCL Music alumni and staff held a reunion dinner at King's attended by over 50 people; and in 2004 KCL published an excellent book entitled In the service of society by Christine Kenyon Jones, which had a large feature on Dart's time at King's.

The next major development in the Dart story was the discovery that the ornate trunk in the room Dart had used at Bill Oxenbury's flat was full of Dartiana that had lain undisturbed for well over thirty years. After Bill moved out in 2005 the contents were eventually given to me. This collection of "Objets Dart" was to form the basis of the Thurston Dart Archive at Cambridge University Library. The unfinished book on John Bull (which Bill Oxenbury had loaned to Susi Jeans some time after Dart's death) has now been reunited with his other papers in the Archive, having been donated by the Library of the Royal College of Organists, where it had resided with the Jeans nachlass. Dart had done five chapters but was not satisfied with it and had not had much time to work on it in his last years.

The Archive was launched in 2014 to a full house at a meeting of The Friends of Cambridge University Library. Christopher Hogwood and I were the keynote speakers and Margaret Faultless (baroque violin), Emily Ashton (viola da gamba) and Francis Knights (spinet) the performers.

Since the opening of the Archive I have had numerous responses from around the world. The late Sir Neville Marriner wrote to me that the Dart Archive was "such a good idea, he was such an influence". Documents in the Archive have already proved valuable in the identification of the provenance of instruments that Dart once owned which are now scattered round the world.

A very welcome extensive biographical article by Ed Breen for the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Music Faculty at King's College, London was researched in the Archive and published in 2015. It gives an in-depth account of Dart's creation and administration of the new KCL Music courses he set up.

It is a measure of Dart's importance that at Christopher Hogwood's memorial service in 2015 both speakers referred to the significant influence of Dart. Catherine Bott quoted Chris as saying (on Radio 3's Early Music Show in 2010), when she asked him how he would like to be remembered, "I think I would like to leave some enduring footprint - one foot in performance and one foot in the science of it, because I think they've been unnaturally separated by university and conservatoire for too long. So I could have the same effect on upcoming musicans as Thurston Dart had on me … I think the performer and the scholar can, and they should be, one and the same person."

In the July 2017 issue of the National Early Music Association UK newsletter Peter Holman (a fellow student with me at KCL) cited him as a principal influence. Undoubtedly Thurston Dart is now being fully recognised as the major historical figure that he was.

This article first appeared in Volume i/2 (July 2017) of the NEMA newsletter.

Copyright Greg Holt © 2006-11